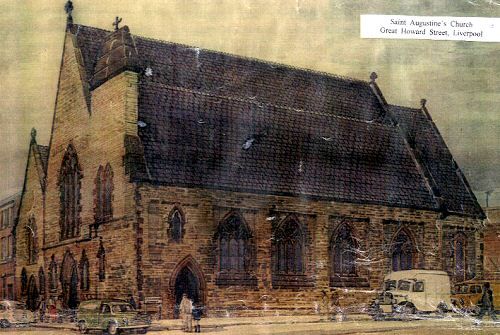

Not to be confused with the Church of England’s St Augustine’s, built in 1836 in Shaw Street, Liverpool (a Victorian pile in a posh part of town) and destroyed in a Luftwaffe bombing raid in 1941, Everton St Augustine was a jewel in the crown of the Irish Roman Catholic community for many generations. It was opened and dedicated in 1849 as a “Chapel of Ease” to St Mary’s Church – a large and well-established parish – just half a mile away. (A Chapel of Ease is defined as a place of worship built within the bounds of a parish for those parishioners who found it difficult to make the journey to the parish church.) It was given the unofficial title of “The Martyrs’ Church,” in memory of the Benedictine monks who died in Everton during a typhoid epidemic in 1847.

A few historical observations from this time. Firstly, it is shocking (and that is a gross understatement) to read about how many tens of thousands of poor people, predominantly Irish, died from virulent diseases such as typhoid, cholera, smallpox – and from malnutrition. The Irish immigrant communities of Everton and neighboring Toxteth were decimated by such.

Second, the political elites of the day saw no benefit in improving social conditions but rather put the blame in the “perceived” inherent deficiencies of specific races. And the Irish took the brunt of this. Writing in his 1840 pamphlet Chartism (supposedly a working-class movement for reform) Thomas Carlyle declared:

Crowds of miserable Irish darken all our towns. The wild Milesian features, looking false ingenuity, restlessness, unreason, misery and mockery, salute you on all highways and byways. The English coachman, as he whirls past, lashes the Milesian with his whip, curses him with his tongue; the Milesian is holding out his hat to beg. He is the sorest evil this country has to strive with. In his rags and laughing savagery, he is there to undertake all work that can be done by mere strength of hand and back; for wages that will purchase him potatoes. He needs only salt for condiment; he lodges to his mind in any pighutch or doghutch, roosts in outhouses; and wears a suit of tatters, the getting off and on of which is said to be a difficult operation, transacted only in festivals and the hightides of the calendar. The Saxon man if he cannot work on these terms, finds no work. He too may be ignorant; but he has not sunk from decent manhood to squalid apehood: he cannot continue there. American forests lie untilled across the ocean; the uncivilised Irishman, not by his strength but by the opposite of strength, drives out the Saxon native, takes possession in his room. There abides he, in his squalor and unreason, in his falsity and drunken violence, as the ready-made nucleus of degradation and disorder.

Such blatant prejudice and discrimination clearly created Irish communities that were self-reliant in matters of body and soul. Within a year of its dedication St Augustine’s Church had over 16,000 enrolled parishioners! Such was its explosive growth that it was declared a parish within its own right and ceded from St Mary’s parish. A Father Cook from the St Mary’s team became the first parish priest.

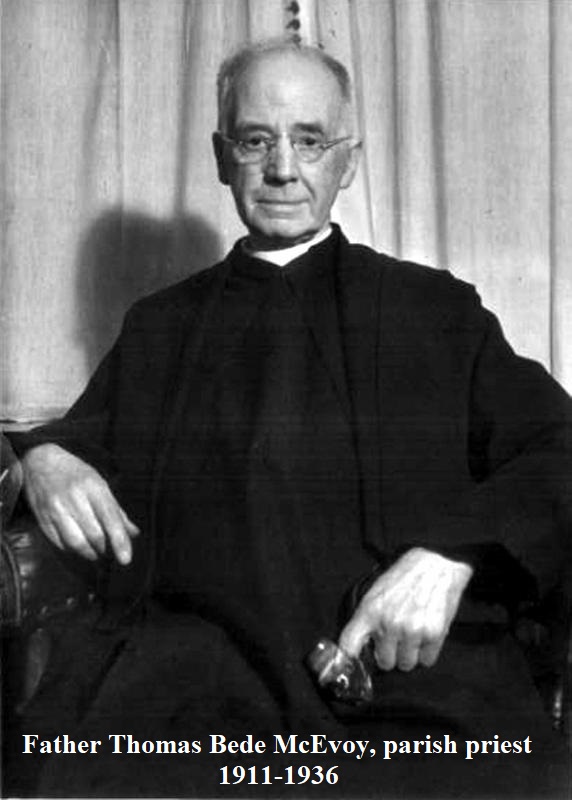

There is little documentation of this parish over the next century – the notable exception being the ministry of one Father Thomas Bede McEvoy, OSB who arrived in 1911 and served twenty-five years as parish priest.

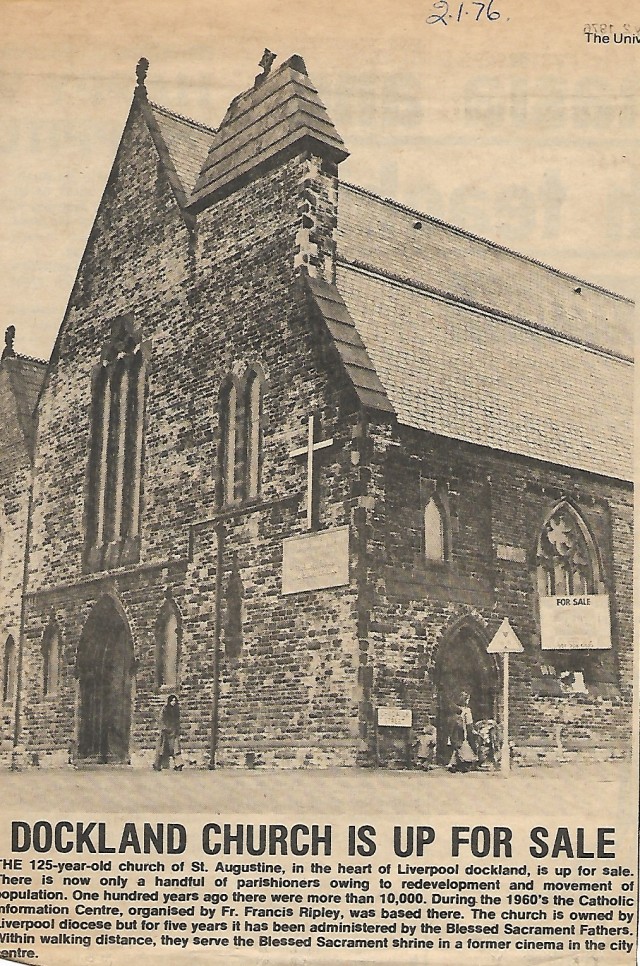

What is apparent is that St Augustine’s began a dramatic decline in parishioners at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1910 its membership had fallen to under 3000, with no sign of recovery.

Two things were happening. The population of the parish was gradually moving out, and industry was moving in. In 1938 it was decided to demolish most of the houses and other buildings, that “This district … become an industrial area.” (Ministry Certificate of Demolition.)

World War Two arrived shortly after this, and subsequent air raids destroyed a great deal more. There were still a significant number of families living in the parish, and some lost their lives by staying. After the end of the war most relocated to new housing estates built on the outskirts of Liverpool.

The church somehow remained. I have not been able to unearth any information for the 1950s and 1960s (yet) but I will keep digging.

A newspaper cutting, dated January 2nd, 1976 and discovered in a recently purchased copy of Arthur Mee’s Lancashire announced that St Augustine’s was up for sale. “Now only a handful of parishioners owing to redevelopment and movement of population.”

In memory of this once thriving parish, which served the spiritual and physical needs of thousands, I post a small selection of images culled from the web. And if you scroll down to the bottom of this post – the site of St Augustine’s Church today.